Towards the end of it The Last Samurai, Helen DeWitt's 2000 novel about a single mother and son who bounce around the poverty line as the latter searches for a suitable father figure, this son converses with a brilliant but difficult pianist. “Why don't you make a CD?” the son asks. The pianist replies: “No one would buy what I wanted to put on a CD, and I can't afford to make a CD that no one will buy.” The Last Samurai hailed by critics and sold over 100,000 copies. But due to mathematical conventions that would make Q-Tip blush, DeWitt concluded due its publisher's money. In no time, the book sold out. In the decades since, DeWitt's fiction has focused on the material lives of artists as they struggle to navigate capitalism and psychological breakdown.

Once a rising pop star and critical darling with a seemingly clean trajectory, Lupe Fiasco has seen his career similarly tangled over the past 15 years. Since the public feud between him and his former label, Atlantic, over his third album in 2011 Laser, Lupe remained near the top of the list due to fame, but plummeted chart positions suggesting an audience separated from the rap mainstream. He spoke often and eloquently not only about the business details that complicated his decision-making, but also about the ways in which hip-hop — and music writ large — is discredited compared to so-called fine art. (“If I want to read Helen DeWitt's next book, I can just write it, read it, and then write another,” the Last Samurai said the author The believer in 2012. “Painters do this and no one objects.”)

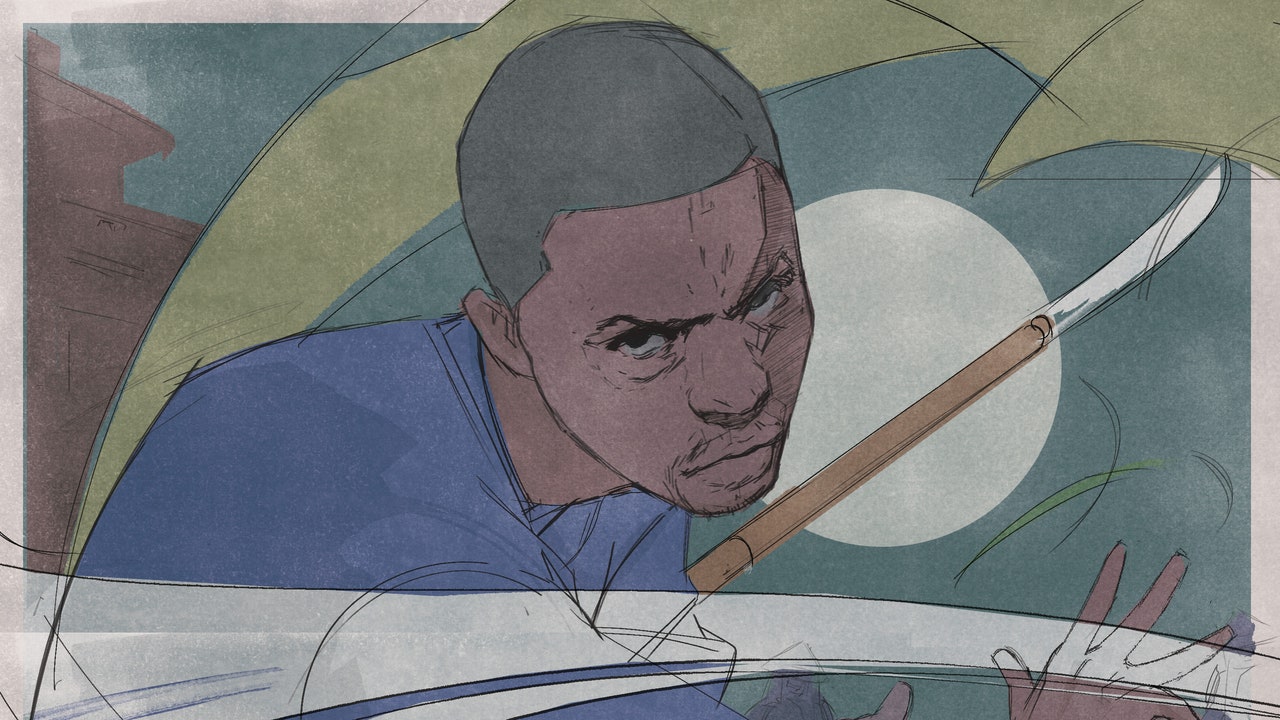

Samuraicoming nearly two years after Lupe's eighth album, Drill music in Zion, has a lot in common with this project: It's produced entirely by longtime collaborator Soundtrakk, it's jazzy and understated, and it's light (even lighter, in fact, at just 30 minutes). Its title was inspired by a moment in Asif Kapadia's 2015 Amy Winehouse documentary in which the late singer leaves a voicemail to producer Salaam Remi, describing herself as a samurai battle rapper. For Lupe, the metaphor seems neat: a motivated teacher working in relative isolation, sharpening a blade.

The album is obviously cool. Lupe's singing voice, a staple of his style long ago The Cool, has become more malleable: See the way he moves between rhythms and harmonies in the hook and verses of “Palaces,” each cleverly shaped and carefully delivered. Elsewhere it flits, without apparent effort, among other modes of technical wizardry, such as the staccato grid of syllables that clothes the prose in the second verse of “No. 1 Headband” or the quote on “Mumble Rap” that begins with the line, “With a style akin to hanging around looking for a catch to resist.” It feels like there's some big, centrifugal force pushing down on the middle of each bar.

And yet this musical ease seems deliberately at odds with the torture Lupe describes, in first and third person, of trying to hack a career in the arts. There are the shows where the “front row the only row” (“Bigfoot”). there's the line in “Out” where he says, “My business bone is tied to my ethics”—provocative from one angle, quixotic from another. Lupe zooms in and out of Amy Winehouse's portrait, and when she raps, on closer “Til Eternity,” about a beehive that “survived a wreck,” it's both a reference to her signature hairstyle and a metaphor that echoes those introduces. earlier on the album. “We think we're fortresses, made of stone,” croons “Palaces,” “but we're just palaces made of flesh and blood.” Despite the grandeur of the “palace,” it presents this fragility without romance — or at least, fully aware of the forces conspiring to puncture it at every turn.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you purchase something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.