On May 8, 1965, a group of musicians gathered in a house on the South Side of Chicago. They had been invited there, via postcards mailed by four local colleagues, to discuss the formation of a new collective, dedicated to creating new opportunities for artists involved in what they called, simply, “creative music”.

At one point during the meeting, a saxophonist named Gene Easton summed up the frustrations shared by many in attendance. “We're locked into a system,” he said, “and if you don't express yourself in the system that's known, you're ostracized.”

“But,” he added, “there are much better systems.”

By this time, a few prominent musicians had famously subverted the conventions of mainstream jazz, pursuing revolutions either subtle or explosive (see Miles Davis Type Blue and Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Comerespectively). But the change in jazz continued to be accompanied by controversy: John Coltrane, for example, alienated some critics and colleagues with an increasingly abstract style. For an average working jazz musician, especially outside of downtown New York, who wanted to keep playing while aspiring to dabble in the avant-garde sounds—let alone someone who, like some present at that 1965 South Side meeting , was wary of pledging allegiance to jazz or any other style—it's easy to see why open expression is still dangerous.

When Easton talked about feeling “locked in,” he was talking in musical terms. But his desire to transcend creative limitation meant a higher purpose for the nascent Chicago collective, one that would open new avenues for black musicians seeking to thrive beyond category or genre. The group, soon to be called the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, or AACM, would go on to have an immeasurable impact on the course of jazz, experimental music, modern classical, and other proudly unclassifiable styles from within. 1960s to today.

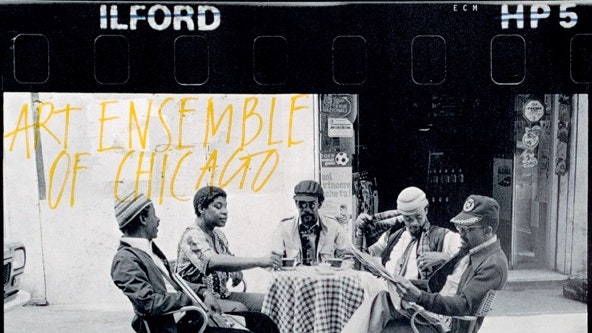

A short list of major artists to emerge from the AACM includes two Pulitzer Prize honorees (2016 winner Henry Threadgill and 2013 finalist Wadada Leo Smith), various NEA Jazz Masters (including Muhal Richard Abrams, co-founder of the group and longtime musical and intellectual anchor, as well as Anthony Braxton, Amina Claudine Myers and Threadgill) and younger luminaries such as Nicole Mitchell, guitarist Jeff Parker and cellist Tomeka Reid. But of all the musicians who have ever flown the banner for the best system of organization, perhaps none embodied the basic principles of unlimited aesthetics, self-determination, and solidarity among individuals more aptly than Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, Malachi Favors, and Lester Bowie. early members who eventually joined forces as the Art Ensemble of Chicago.