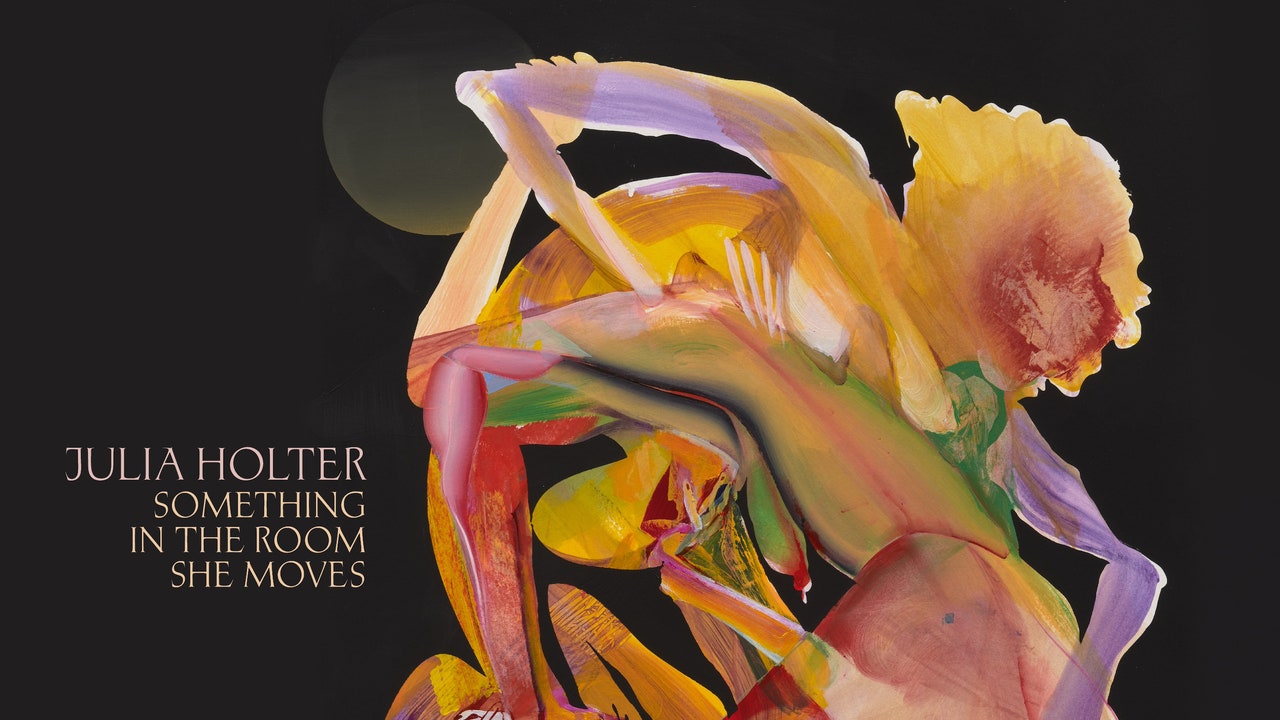

In early 2020, while Julia Holter was working on a relatively quick follow-up to her 2018 project, Poultry farm, two complications arose. The first, a pandemic, you know everything. the second, a pregnancy in lockdown – well, imagine. The change threw this once prolific singer-songwriter into a period of stops and starts. He stopped playing, of course, and mostly stopped writing songs. perhaps most seriously of all, he stopped reading medieval texts. She started preparing for motherhood, then she stopped preparing – motherhood was here! When she finally started recording, exhausted, things often went wrong: She would stop singing and start yawning, sometimes falling asleep at the controls. This was not a reflection of the music, although it is true Something in the room moving she forgoes her usual song and dance, distilling her troubled creation into a long, boring thought. Stop talking, he suggests, and start listening.

In the 13 years since then Tragedy, her bold, Euripidean debut, Holter has made the opposite demands of listeners. On the one hand, her work veered towards pop and back again. At the same time, she and her ensemble have drawn a wider arc from intention to intuition. After the early entries of high conception — drawn from Hippolytus, from Gigithe process he calls “mixing texts” — meandering improvisation at the core of Holter's practice, supported by collaborators such as bassist Devin Hoff and multi-instrumentalist Tashi Wada.

His Holter Something in the room moving he sounds more determined than ever to repudiate conscious authorship. The music—bubbly, cloudy, free—seems to have a mind of its own. The idea, if anything, borrows the basic principle of meditative minimalism: Reduce, reduce, reduce to lift your spirit higher. Opener “Sun Girl” is the model in miniature, a bright little odyssey that could fool a conservatory crowd but just as easily reduce—or even raise—a child to rapturous giggles.

In addition to her daughter, Holter dedicates the album to her late nephew, “a handsome young man who loved making art, discussing ideas and was passionate about socialist politics.” In 'Talking to the Whisper', a moment of devastating brilliance, he draws out agitated pleas – 'Heaven can't take my love'. “Love Can Fall Apart” – but the true climax is a cosmic, wordless breakdown that evokes the ecstatic sadness of Alice Coltrane Universal Consciousness. In her recent live for Carl Theodor Dreyer's film The Passion of Joan of Arc, Holter sought a language of unintelligible chants, including “syllables stripped of their word context,” to reflect protagonist Renée Jeanne Falconetti's fidelity to the inexplicable. “Talking to Whisper” and Something in the room moving generally, use a similar lyricism that, like Falconetti's Joan, eschews literal explanation in favor of communion with the sublime.