Jazz, like the world it reflected, was in flux in 1969. That year, Miles Davis released In a quiet way, an album whose low-key vibe belied its status as a harbinger of great upheaval, ushering the music into a decade of electric instruments, studio-driven experimentation, and rhythms drawn from funk and R&B as much as swing. However, many people still played changes the old-fashioned way: a musician could devote his entire life to mastering the craft, and just because Miles was suddenly manipulating tapes and listening to Sly and the Family Stone didn't mean everyone else followed his example. And free jazz, a decade or so at that point, was still a radical force, its elaborations and deconstructions of melody providing alternative routes forward from tradition, ones that didn't necessarily require connection.

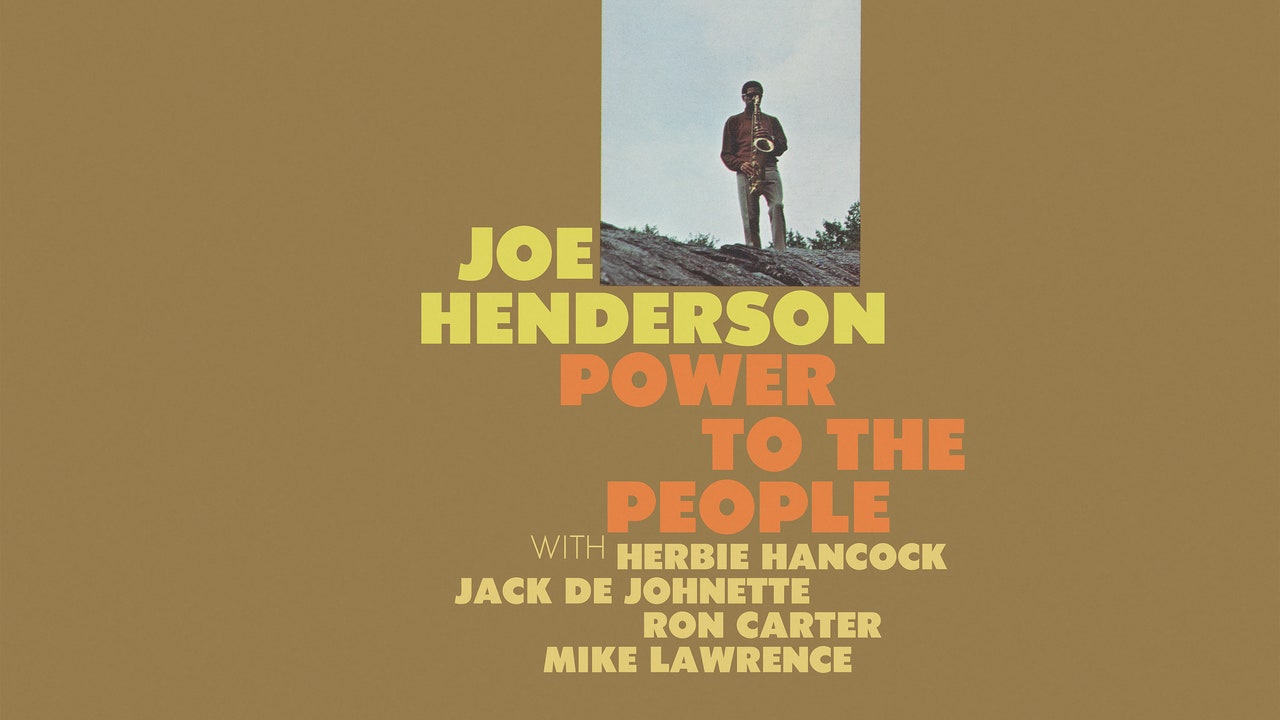

Looking back, it's tempting to see these various styles – fusion, straight-ahead, avant-garde – as completely separate and walled off, and it's true that some players could be dogmatic in their adherence to one idiom and rejection of the others . The case of tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson provides good reason to consider them more holistically. An old-school virtuoso who learned to play by transcribing and memorizing solos from bebop titans like Charlie Parker and Lester Young, he also dabbled in free jazz as a sideman with Andrew Hill and encouraged his own players to experiment with electronics. even on discs that avoided full-on fusion. His 1969 album Power to the people, Available on vinyl for the first time in decades via a superb new reissue from Craft Recordings and Jazz Dispensary, it's an essential document of this transitional moment, in part because of its creator's indifference to its rigid stylistic affiliation. If you want to hear, on a single album, what jazz sounded like – all of it – just before the turn of the '70s, you could do worse than this.

Henderson was surrounded by some of the best players in the world Power to the people. Two, Herbie Hancock and bassist Ron Carter, were veterans of Davis's band, and one, drummer Jack DeJohnette, had just joined Miles around the same time. Henderson also enlisted up-and-coming trumpeter Mike Lawrence on two of the seven tracks. Throughout the album, Hancock switches between acoustic piano and Fender Rhodes, and Carter between upright and electric bass, choices that reflect the album's fluid stylistic approach. Carter's choice of basses, in particular, is a rough indication of where a particular track will fall on the spectrum. On the upright, his main instrument, he tends toward traditional walking lines, outlining the chords with a steady pulse that the rest of the players are free to improvise around. On the electrics, he dances more freely on the edges of the pocket, poking in and out in search of new rhythmic possibilities, pushing the music away from the well-worn solo and accompaniment format of jazz and toward a more open group improvisation.